Traveling with Cancer: The Real Deal with Meg Stafford

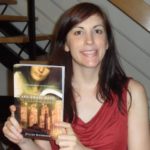

Does confronting cancer mean that one’s life revolves solely around the illness? This question and many more have been the preoccupation of writer and traveler Meg Stafford. While Meg was contemplating these concerns and going through treatment, she was also traveling and embracing life to the fullest. With the goal of helping others do the same, Meg wrote about her experiences and shared some of her tips in her memoir, Topic of Cancer – Riding the Waves of the Big C. We had the pleasure of speaking with Meg.

Traveling, writing, and thriving all while battling breast cancer: you are an inspiration! How do you do it all?

A big part of what helped me during treatment actually was my writing. There was so much information to gather, and I was happy to share any or all of it, but the thing I couldn’t stomach was telling it over and over. It started as an email distribution list to keep interested people updated, and it truly became a two-way permeable membrane of love and support. By writing about what was happening, it enabled me to let go of each experience (as much as I could) as it arose, freeing me for the next wave (or tsunami).

There wasn’t too much travel during the most intense part of treatment, but right after I finished my last reconstruction, my daughter in college was going to a field-work term in Peru. Machu Picchu was a dream site to visit, and I focused on this as an end-of-treatment celebration trip, as we were able to visit about six weeks after my surgery.

I am so impressed and moved by your memoir Topic of Cancer – Riding the Waves of the Big C. Could you tell our readers a bit about it?

I started hearing back from people when I wrote, some telling me that they now understood what their mother/cousin/sister had gone through but hadn’t been able to talk about. I started including my thoughts about whatever else was going on in my life, which happened to be quite eventful during that 18 months. People were kind about tolerating my puns (or even encouraging this oft-maligned behavior) and began telling me that, oddly, they missed the days when I wasn’t writing. Some also admitted that should they, or someone close, be diagnosed, they now felt they could handle it, or know how to help their loved one.

What was the most challenging part of facing breast cancer?

I knew from the beginning that my prognosis was really good, and because of some scary childhood events with unexpected deaths, I had already hopped on the train of appreciating life. What was challenging for me was accepting help gracefully. People show kindness in many different forms, and it was important for me to honor whichever ways people showed up, even if I was not expecting it.

Being a mom and a social worker, the role of the caregiver was much more familiar, and I had to learn to be the person needing help. There were times when I had to embrace my inner sloth, which is not natural to me. I am more of a monkey.

One of the most beautiful parts of your book is how you focus on living and not just surviving. Could you speak to this decision and way of being?

Thank you for asking in this lovely way. I was about to say that it was not a conscious decision, but I’m realizing that I bullheadedly insisted that the cancer treatment not fill the frame of my life. At times, it had to be front and center (like the days I was in chemotherapy or on surgery days), but other than that, it was important to me to be living my life, and having the treatment be a part of it.

I actually chose to have my first round of chemotherapy spaced three weeks apart instead of two, because in that third week, I could live my life almost completely normally: biking 15 or 20 miles a few times, working my three days, walking the dog, going out to dinner. It meant that it protracted the total time of chemotherapy by more than a month, but it was worth it to me to have those “normal” weeks.

My daughters were 12 and 17 when I was diagnosed, and there was lots going on with them. I did not see myself as primarily a cancer patient. I saw myself as a person living my life who was also having cancer treatment.

I am also interested in your writing process. Do you have a routine?

During my treatment, I wrote frequently, because I needed to, usually in the evening in the office looking out at the trees in front of our house. Now I write primarily for my monthly newspaper column, A Moment’s Notice, about whatever grabs me at the time. Usually there is something that I just have to get out because it’s swirling around in my head and I need to figure it out, or share my thoughts, and I’m restless until I do so.

I write longhand first, because I love the physical act of writing. The first edit is when I get it into the computer. After a few more edits, I print it out. Next I read it out loud to whomever I can recruit. It’s still a challenge for me to be more disciplined about writing more regularly, even when there is not something jumping up and down, ready to spill out.

Are there specific places that you find to be more conducive to writing?

I love to write at our kitchen island now. I can still see those lovely trees out the front and side of the house. I have always loved to write outside: by a pond, in the mountains, by the sea. There is something so expansive about being outdoors and feeling the air on my face, smelling the sea or the pines. It helps me to drop into a place of concentration and openness to get to what is most cogent.

I’m actually considering renting a small office in town because at home I’m offered multiple distractions in the form of our two energetic dogs, orange Maine Coon cat, and the inviting fridge with its enticing leftovers, or even the laundry that rolls its eyes at me.

What is the biggest piece of advice you would give to women battling cancer?

Everyone has to listen to his or her own counsel during treatment. No two situations are alike, in terms of accessibility to treatment, age, overall health, level of nearby support, etc., and I might make different choices now than I did 10 years ago. What’s right for one person may be decidedly repulsive to another, and it’s a great thing that there are often options about the way to proceed, even if that in itself is sometimes daunting.

Learning to pay attention to what feels best can take some practice, and it can be helpful to have someone to talk with about making sure the volume is boosted on one’s own voice. It is also important to remember that there are choices about health care providers. There were a couple of times when it took more than one consultation to get to the person with whom I felt most comfortable. Being able to trust my treatment team meant that I was freed up to think about the really critical stuff, like whether I wanted to leave my wig on the lamp by the table, or the one near the fireplace. Or whether I wanted a ginger cookie, hard candy or tunafish to handle tastebud demands.