What I Learned on My Reluctant Visit to Hiroshima

I had mixed feelings about visiting Hiroshima and initially decided not to go. I know a lot about the atomic bomb attacks on Japan. Back in the early 90s, I attended a three-week intensive workshop for teachers about nuclear issues. I learned about the science of the various kinds of nuclear weapons, the mathematics of radiation and half-lives, and about the effects of bombs: blast effects, thermal effects, fallout and long-term radiation effects.

Additionally, I learned about the Cold War and the nuclear weapons buildup as well as about efforts to limit proliferation.

I decided to go because a friend insisted it was worth doing. He was right.

Not only that, after that workshop, I used what I’d learned to produce my final project for my first Master’s degree. I produced a six-week interdisciplinary curriculum about nuclear issues for use in secondary schools. It included chapters for students to read about the science, the politics, and the history. I filled it out with worksheets to accompany the chapters, project assignments, and materials for teachers, including a video, to use in lessons to help illustrate the concepts.

So I figured I already knew whatever the museum in Hiroshima was likely to show me.

I decided to go because a friend insisted it was worth doing. He was right.

Ground Zero

As I walked through the city on my way to the Peace Memorial Park, I thought about what it must be like to live in Hiroshima today. Known outside Japan solely for being the target of the first use of nuclear weapons on humans, it manages not to be only about that. It’s a modern city, like Tokyo or any other bigger city in Japan.

Young women dress in the sorts of extreme outfits we associate with Tokyo. Restaurants promote a local specialty, okonomiyaki, a sort of savory pancake with everything on it, plus barbeque sauce. It’s an ordinary Japanese city.

I passed a sign indicating Ground Zero; 600 meters in the air above that spot, the bomb had detonated. It seemed such an ordinary place. Looking at it, you’d never guess something so horrific had ever happened there.

I walked to the nearest intersection and filmed it.

The Atomic Bomb Dome

Right near Ground Zero stands the Atomic Bomb Dome, the most famous image of post-bombing Hiroshima. It’s ironic that this image is of a building that’s partially intact while virtually all buildings within two kilometers and 2/3 of the buildings in the city as a whole were destroyed completely.

I knew about this building but didn’t expect the feeling that hit me when I saw it in person. I felt, I realized, like I felt when I visited Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Museum, in Israel. It’s the randomness of the deed: the indiscriminate nature of a massacre, the unfairness of its “choice” of victims.

Fighting tears, I sat on a low stone wall under the trees next to the Dome. An old woman rested nearby on a bench and, using hand gestures, insisted that I join her on the bench rather than the stone wall. At her age, she could be a survivor of the attack, or have been born soon after.

It’s the randomness of the deed: the indiscriminate nature of a massacre, the unfairness of its “choice” of victims.

Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall

Next I walked through Peace Memorial Park, a pleasant piece of green between two rivers. It holds a number of different memorials. I visited the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims. At the entrance stands a fountain in the shape of a clock set to 8:15, the moment when the bomb was dropped. The water tumbles over a collection of debris: A-bombed roof tiles.

Entering the hall, visitors follow a circular ramp into a sunken room. Round, tile-lined, with another small fountain in the middle, again set to 8:15: this is the Hall of Remembrance. The wall shows a circular panorama of Hiroshima after the blast, and is composed of 140,000 tiles to represent the 140,000 people who died between August 6, 1945, the day the bomb was dropped, and the end of 1945.

The hall is a hushed place, intended for prayer and meditation to the sound of the trickling water. The water imagery built into this memorial building is a reference to the victims who died crying out for water.

Check out Pink Pangea’s Writing, Yoga, and Meditation Retreats.

Peace Memorial Park

Also in Peace Memorial Park, the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims contains a sort of sarcophagus with the names of all the known victims. The shape of this memorial allows a view of the Dome in the distance, tying the victims directly to that image.

Another monument nearby is a burial mound covering the ashes of people who could not be identified. Imagine that: having nothing to bury.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

The Dome and the Cenotaph, along with an eternal flame—which will only be extinguished when all nuclear weapons have been destroyed—line up with the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, forming a stark, powerful image.

The museum charges a token entry fee (50 yen, which is about 35 eurocents, but free for groups). It consists of several parts: a section on Hiroshima before the explosion, a section on the attack itself and its effects, and a section on the nuclear age.

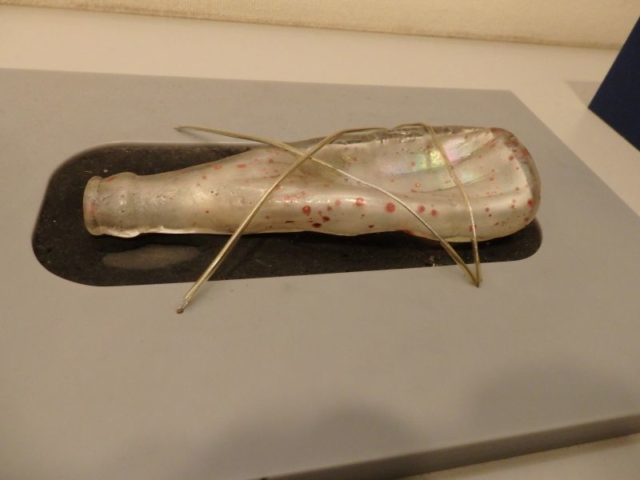

Unfortunately, on the day I visited, only the part about the attack itself was open while the others were being renovated. I shuffled through a series of displays about what happened that day. Many of the artifacts came from schoolchildren who had been mobilized that morning to help tear down buildings to set up fire lanes.

Burned pieces of clothing, a lunch box, a watch, shoes, and so on: normal, everyday items that were retrieved after the event and often saved by the grieving families. With each item, the accompanying text names the victim and tells what he or she was doing when the bomb dropped and how he or she died.

I had seen photos of many of these items, but somehow, seeing them there, so ordinary, made it feel much more real. Again, (or, perhaps, still) I fought back tears.

Photos of burn victims and a piece of a building where a human shadow is visible illustrate the thermal (heat) effects of the blast.

The museum then took visitors through displays explaining the various effects of nuclear weapons. To illustrate the force of the blast, for example, the display showed bent steel beams from one of the destroyed buildings. Photos of burn victims and a piece of a building where a human shadow is visible illustrate the thermal (heat) effects of the blast. And so on.

Many people learn about the Hiroshima bomb through the story of Sadako Sasaki in a children’s book, Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes, by Eleanor Coerr. Her particular story is told in a separate display in the museum, which also serves to show the longer-term effects of the radiation: she was two years old and was about two kilometers away from Ground Zero on the day of the bombing.

She died of leukemia at 12 years old in 1955 as a result of her exposure to radiation.

What made Hiroshima worth visiting was that it made me feel something about it again.

Again, this was all information that I knew. I put chapters about all of the effects in the science section of my curriculum. I suggested an activity in which students use maps of a hypothetical bombing near them to figure out what the different effects would be at their particular distance from Ground Zero.

In fact, I recommended that teachers use the children’s book about Sadako along with John Hersey’s Hiroshima as texts for the English component.

I didn’t learn anything new. Instead, what made Hiroshima worth visiting was that it made me feel something about it again. This is, of course, the intention of the people of Hiroshima to this day: to make visitors feel strongly enough about nuclear weapons to inspire them to prevent anything like this from ever happening again.

I sincerely hope they succeed. At the same time, I feel extremely pessimistic about its chances for success.

What I Learned on My Reluctant Visit to Hiroshima was first published on Rachel’s Ruminations on August 6, 2015.

What I Learned on My Reluctant Visit to Hiroshima

Have you traveled to Hiroshima? What were your impressions? Email us at [email protected] for information about sharing your experience and advice with the Pink Pangea community. We can’t wait to hear from you.

Photo by Rachel Heller and Unsplash.