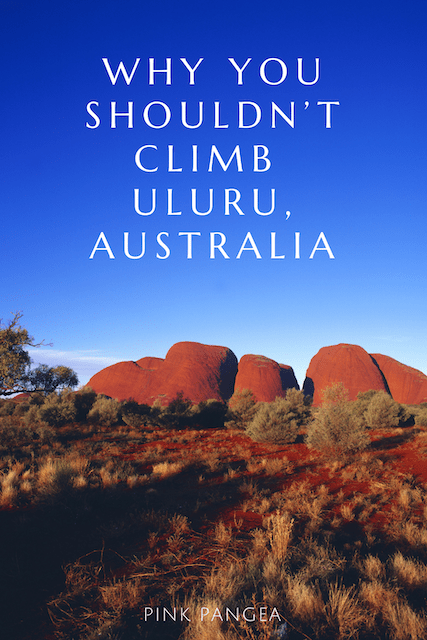

Why You Shouldn’t Climb Uluru, Australia

When planning a family trip to Australia, the only place my mother insisted we include on our itinerary was Uluru. I’m embarrassed to admit that I had never heard of Uluru at the time, but I’m so glad that we made it our first stop during our two weeks in Australia.

Uluru is the aboriginal name for the massive rock formation in Australia’s Northern Territory, which is also known as Ayers Rock, the name given to it by an Australian explorer when he “discovered” it in the late 1800s. Located in the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, Uluru and Kata Tjuta (the other rock formation in the park) are special places to visit. Both are sacred to the Anangu, the aboriginal Australians native to the region.

On our first night in Australia we were treated to a sunset tour of Uluru organized by our hotel, Longitude 131°. “It’s not a true sunset without some bubbly!” quipped our tour guide, as we stood at Uluru’s base. We had just finished a partial walk around the sandstone rock and were admiring how its façade was changing color from tan to red as the sun dipped lower and lower on the horizon.

The aboriginal Anangu do not want people to climb Uluru, which is 348 meters (or about 1,142 feet) tall…but Parks Australia allows climbing as long as weather conditions are calm and despite the fact that some deaths have resulted from people attempting the climb.

While the sunset was beautiful, I believe that Uluru is most stunning first thing in the morning. As the sun rises across the desert, it turns the sky magnificent shades of purple and pink and the rock seems to glow a shade of red that is hard to capture in pictures. Driving into the park at this time every morning I was transfixed, staring at the structure and marveling at the constantly changing light in the sky. Despite the early hour, a trip to Uluru would not be complete without witnessing dawn’s first light.

Check out Pink Pangea’s Writing, Yoga, and Meditation Retreats.

What struck me even more than the sunrises and sunsets, though, is the history of the Anangu people and learning all of the reasons why Uluru is sacred to them. As we walked around Uluru, we were told the Anangu’s creation stories, and how they believe that different places on the rock were formed by the actions of the animals that lived on the land before they did.

The art that is found etched onto the walls of the numerous caves and overhangs on Uluru tell some of these stories, and more. Our guides helped us decipher different images: concentric circles typically represent a place, like a watering hole, where people and animals gathered, and configurations of lines signify animal tracks and hunting stories. In certain areas, European explorers attempted to wash away the drawings and writing depicting the Anangu history. Fortunately, they were not able to completely erase the images and many of the markings remain visible.

When I learned about the history of the European explorers at Uluru, it immediately brought to mind the plight of Native Americans in the United States, and how American settlers forced them off their native land. In the early 1900s, the Australian government claimed ownership of the land traditionally inhabited by the Anangu, which is now Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. Under government ownership, tourism increased to Uluru in the 1950s. It wasn’t until the 1980s that ownership of the land was returned to the Anangu in a formal government ceremony.

We watched a video of this ceremony when visiting the Cultural Centre located within Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park (a worthwhile detour for any visitors). It was an incredibly powerful moment, but one that should never have been necessary. When the land was transferred back to the Anangu, the agreement was that Parks Australia would share management of the park with the Anangu and that the Anangu would lease the park back to the Australian government for 99 years.

A visit to Uluru means sharing a sacred place with the Anangu. I believe that as visitors to their land, we have an obligation to abide by the requests that the Anangu make of us, including not climbing Uluru and not photographing certain special areas of the rock.

One of the ways in which the Anangu’s view of Uluru as sacred has clashed with the co-management arrangement of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park with Parks Australia is that the Anangu do not want people to climb Uluru, which is 348 meters (or about 1,142 feet) tall. Parks Australia allows climbing as long as weather conditions are calm and despite the fact that some deaths have resulted from people attempting the climb.

When I heard that the Anangu request people to honor Uluru and refrain from climbing, both out of respect for their culture and concern for our own safety, I immediately understood and did not want to attempt a climb. It astounds me that knowing this, many people still climb the rock every year, against the express wishes of the people on whose land we walk.

A visit to Uluru means sharing a sacred place with the Anangu. I believe that as visitors to their land, we have an obligation to abide by the requests that the Anangu make of us, including not climbing Uluru and not photographing certain special areas of the rock, as I saw some of my fellow travelers attempting to do.

These are simple requests that do not seriously inconvenience visitors. Visiting was an experience that reminded me of how small a part of our world I actually am, and yet how interconnected all of our life experiences and histories are.

Why You Shouldn’t Climb Uluru, Australia photo credits by Unsplash.