Dromedary Dreams in the Sinai Desert, Egypt

“The lightly burdened shall be saved.” – Bedouin Proverb

Bedouin means “Badiyah dwellers” in Arabic – Badiyah literally meaning “the visible land” – but they call themselves El Arab. Nomadic herders from Arabia, Bedouin are scattered across deserts, including what is now the Egyptian Sinai Desert.

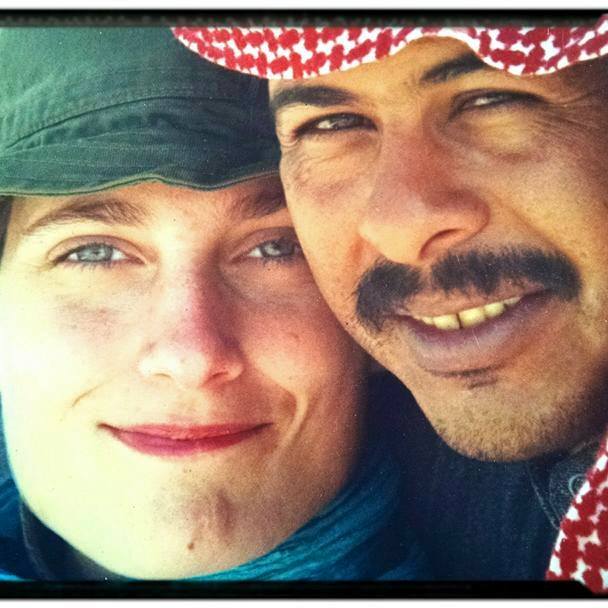

For many, the word ‘desert’ may conjure a barren wasteland, a state of desolation, abandonment. This is in stark contrast to the glimpse I got of a world rich with beauty and mystery over a two-week long trekking journey in the southern Sinai, led by Muzeina Bedouins. This journey began at the end of a (sometimes grueling) introduction to my fiancée’s extended family in Israel. I was excited for the chance to break away and experience Middle Eastern culture outside the tensions of urban Jerusalem.

In a place where houses are considered graves for the living, you are never “at home,” nor are you ever away from it. It’s only natural that the tradition of Bedouins acting as guides goes back centuries – traders, pilgrims and explorers alike relied on their intimate knowledge. Most Bedouin navigation – at least in the southern Sinai – is from memory.

In a place where houses are considered graves for the living, you are never “at home,” nor are you ever away from it.

We traversed on foot and by jeep to take in the drama of Masada, float in the Dead Sea, and snorkel one of the world’s most diverse barrier reefs at Sharm el Sheikh. We camped at night by the fire as the guides brewed tea, black and sugary, poured into shot glasses, and tortilla-like fetir, while smoking hand-rolled khudaree as they shared poetry, stories and songs. This was Bedouin hospitality in action; more than just friendliness, the gift of welcome is more valuable than gold. If you don’t say hamdulelah – thank God – when you’ve had enough food, you’ll just be given more.

Bedouins bring the desert world to vivid life through a long tradition of music and oral poetry. For example, one singular subject, the Arabian camel, illustrates the richness of this tradition. Camels are more than sources of food, transportation and livelihoods, they are close companions too. Songs are composed and sung just for them. In fact, more than one joke was told about the jealousy of wives over the attention showered upon a favorite camel.

The number of words to describe camels in pre-Islamic Bedouin language exceeds one thousand. Our guide, Kaleb, shared that in addition to words describing the sex, color, size and temperament of camels, there are also words to capture specific camel manifestations.

To illustrate, he pointed to one nearby that was resting on her knees: baraka describes the action of a camel kneeling. But there’s more. She’s a female camel resting. (Another name). She’s a female camel resting, who doesn’t drink from the watering hole when busy, but waits and observes. (Another name). She’s a female camel resting, who doesn’t drink from the watering hole when busy, but also a female camel that produces froth when milked. I got the idea, and came to learn a lot more than I ever imagined about the way of dromedaries.

More than one joke was told about the jealousy of wives over the attention showered upon a favorite camel.

Home to the Burning Bush, St. Catherine’s Monastery was the last stop on our journey. Built by Roman Emperor Justinian in the sixth century, it sits at the foot of Mount Sinai, known as Gabal Musa (the Mountain of God), the birthplace of Judeo-Christianity. Part of the monastery experience is to climb the craggy, sheer faced massif 7,500 feet above sea level, usually overnight, in order to fully appreciate the majesty of the summit at daybreak.

Fair enough. We set off at 10pm sporting headlamps and swaddled in layers. After three hours, I was fatigued. We reached a rest stop of sorts, and a Bedouin man with camel in tow approached me. We quickly arrived at an arrangement, and with his help, I swung myself up and over the seven feet of furry hump.

Nineteenth century explorer John Lloyd Stephens described Mount Sinai this way: “…among all the stupendous works of Nature, not a place can be selected more fitting for the exhibition of Almighty power.” What he meant became crystal clear the moment I boarded this “ship of the desert.” Suddenly, I was clinging to the mast of a storm – tossed vessel, rudderless, rising and falling in terrifying waves of the oceanic night. I looked over at my guide, who appeared fully relaxed, singing, cooing and clicking in some sort of camelid Morse code.

Dromedary Dreams in the Sinai Desert, Egypt.

My reassurance was shortlived, however, when I glanced over my right side to realize that my 700 pound camel was stepping with hooves all in a single file along the absolute edge of a sheer drop off. For endless hours, we wound our way in the inky blackness up the jagged labyrinth of biblical yore. We were unwitting players in a timeless diorama. As I clung for life to the living, breathing engine of the desert, I was struck by their silhouettes cutting an ancient figure as essential to this monolithic moonscape as the rocks, sand and stars.

Finally reaching the summit, I tumbled off the camel and gave him a hug for bravely bearing me up the mountain. I took my spot on a jagged rock just as the blackness turned deep magenta, crimson, then gold. As my fingers regained their feeling from the heat of the sun, I couldn’t help but wonder how a Bedouin would describe this female person, thawing on top of a mountain, sore but grateful, moved by the mystery of this desert place, the wanderers who animate it, and the dromedary dreams sailing across the sands of time.

Top photo credit for Dromedary Dreams in the Sinai Desert, Egypt by Unsplash.com.