Traveling to Iceland in the Time of Covid-19

Iceland’s policy regarding incoming travel was part of the reason we chose Iceland for this summer vacation.

How Iceland beat Covid-19

According to an article in The New Yorker, even before a single case was identified in Iceland, a system was in place to deal with it, run by police detectives and public health experts rather than by politicians. When cases began to turn up, they were immediately put under quarantine. Detailed tracking traced all contacts, who in turn entered two-week quarantines.

For people in isolation, the approach was proactive: they received regular phone calls asking about their symptoms and whether they needed anything. Keeping a close eye on the vulnerable members of the population in particular meant, in the end, fewer hospital admissions and a very low death rate.

At the same time, testing went ahead on healthy people as well as those who showed symptoms. A biotech firm with a genetic database of Iceland’s population was able to help by tracking tiny mutations in the virus, which offered clues as to how it was spreading.

Iceland has a small population: about 350,000. There was no lockdown, and few businesses were ordered to close. Life went on as normal for those who weren’t quarantined.

Admittedly, Iceland had the advantage, as does, for example, New Zealand, of being isolated to begin with. Once the virus is gone, it’s gone, and no one can sneak across borders and reintroduce it.

Iceland’s reintroduction of tourism

However, Iceland depends on tourism and was understandably eager, like most of the world, to be able to welcome visitors again.

On June 15, Iceland began admitting citizens of Europe, adding other countries later, but at the same time they established a strict protocol to ensure everyone’s safety.

The main element of the new protocol is testing. Everyone entering Iceland has a “choice”: enter quarantine for 14 days, or get tested immediately upon arrival. Written results of tests done at home are not accepted; the procedure must be done by Iceland’s own people at the airport.

These tests have to be paid for, of course, and visiting passengers are the ones who pay. The price was initially the equivalent of about 100 euros, but just a few days before we left for Iceland we learned that we could pre-pay in exchange for a discount. We also had to fill in a form stating where we were planning to stay for the first five days of our trip. Once we’d paid and submitted the form online, we received a bar code as a voucher for the test.

The more people download the app, the more comprehensive the tracking can be.

We were also encouraged to download and use an app called Rakning-19. It gives information and updates about Covid-19 in Iceland and, more importantly, it tracks the user’s movements. The advantage of this is that if someone contracts the virus, the app’s tracking function will allow the government to contact everyone who might have come into contact with that person and have them tested as well. The more people download the app, the more comprehensive the tracking can be.

It makes a lot of sense, especially for travelers like us, since we don’t know the people we come in contact with. Traditional contact tracing – where did you go and who else was there? – wouldn’t work well with us.

So what did this look like for us as arriving passengers?

- Photo credit: Rachel Heller of Rachel’s Ruminations

Schiphol Airport

We flew Icelandair from Amsterdam, a 3¼ hour flight. The train to Schiphol Airport – a trip of just over two hours for us – was relatively empty, and all passengers wore masks, a requirement on public transportation in the Netherlands.

At Schiphol, masks are also required. This seems an obvious rule, given that people pass through the airport from all over the world. What I saw at the airport, though, did not impress me with the level of concern about spreading the virus. I saw numerous airport employees without masks, or with masks that didn’t cover their noses.

Checking bags was self-service. We entered our information on a screen – and I have no idea if the screen had been cleaned between users – to receive a baggage tag, then deposited the luggage in an automated machine that issued a baggage claim check.

Waiting for security, we snaked through the usual line, back and forth: the kind we’re all familiar with. You shuffle along to the left between two ropes. At the end of the room, you do a U-turn into the next row and shuffle along to the right. At the opposite end of the room, you do another U-turn into the next line, and so on. It’s the same tactic they use for the lines at places like Disney.

It’s the same tactic they use for the lines at places like Disney.

Every second line was marked with stickers on the floor indicating the 1½-meter distance required between people. The alternate lines, unmarked, were meant to stay empty. In other words, the U-turns at each end would be wider U’s than usual.

Yet we didn’t only use every second line. For part of the way, the ropes led us into adjoining lines. That meant that even if we were careful and kept 1.5 meters away from the people in front of us and behind us, we could have someone standing right next to us on either side. This completely undermines the whole concept of distancing.

The security workers, though, wore masks and gloves and stood behind plastic windows. They were at least trying to keep their distance and to direct us through security well separated from each other.

Boarding Icelandair

At the gate, the passengers mostly kept their distance, and the gate attendants wore masks. We were called to board only a few rows at a time and, unusually, there was no rush to board or clustering at the gate. All of the passengers wore masks at the gate, though I saw a couple of them pull it off their faces whenever they talked to each other.

As I boarded, the gate attendant told me to scan my own boarding pass. I had to open and show my passport but, surprisingly, I did not have to take off the mask. That meant that nobody in the whole process ever checked that I was who I said I was. Doesn’t this represent a security threat?

Icelandair

Boarding went more smoothly than usual, loading from the rear of the plane. We had more than the usual amount of time to get settled. Normally I feel very rushed and crowded and end up having to duck into my seat to let people pass in the aisle. While we had been called to board by row, evidently not everyone came when called. I still had to let people by a few times, but there wasn’t nearly as much jostling in the aisle as usual.

Boarding was also more orderly because Icelandair only allows under-the-seat bags these days. That doesn’t mean you can’t take a normal carry-on bag, but it will be checked for free. Because of that policy, there was no rush to grab overhead space. We could still use the overhead compartments, but there was plenty of room and no competitive struggle.

After doing my best to keep distanced on the train and in the airport as well as during boarding, I felt uncomfortable that the flight was completely full. It made me feel like all of that effort was for nothing. Yet what else can airlines do? Raise the prices enormously to keep half the seats empty, and hope to get enough people to pay that they won’t go bankrupt?

It made me feel like all of that effort was for nothing.

I knew, though, that modern airplanes have remarkably clean air, replacing it from outside frequently and channeling it through HEPA filters. I also was determined not to use the bathroom on the plane, so I’d used the roomier bathroom in the airport. In fact, I had wipes handy, and used them to clean off my seatbelt, tray table, the arms of my chair, and the seatback screen.

Because it was a relatively short flight, there was no meal or snack service. We took a bottle of water on entering the plane, and that was it.

The aisle, for the most part, stayed clear. The flight attendants occasionally walked through, and a couple of children too, but people mostly avoided going to the toilet or moving at all.

Arrival at Keflavik Airport

Once we landed, we sat and waited on the runway for a time. The problem, according to the pilot, was that another plane, bigger than ours, had arrived before us. The lines for testing had gotten too long, and we had to sit and wait to avoid congestion.

The flight attendants made it clear that they expected us to stay in our seats until we were told that we could leave. This begs another question: how is it better to sit in a full airplane than stand in a full terminal? In my view, there’s not much difference, but I had no choice.

We sat for perhaps a half hour before we were allowed to disembark. That occurred row by row, starting from the front. It was orderly and unrushed, and I wish all flights would disembark this way.

Inside the airport

Still wearing masks, we all walked a route through the airport to join the line waiting for testing. Here the spacing on the line was much more sensible than at Schiphol Airport. Iceland promotes a two-meter distance, which was quite doable the way this line was set up.

It was a long wait. I’d guess it was about 30-45 minutes before we got to the front of the line, where attendants checked that we had our vouchers for the test. Next, we were ushered into another line, but this one was quicker: not more than 15 minutes’ wait to enter one of a row of testing cubicles.

At the line for the test cubicles, by the way, all of the attendants had not just masks, but full PPE, i.e. gowns, booties, masks, shields and gloves.

When I finally stepped into a cubicle, the woman giving my test put gloves on over the gloves she was already wearing. She wore a mask and shield and full PPE. She had me hold my bar code under a scanner, then administered the test quickly and efficiently – and slightly painfully, but it was over quickly. Finished, she waved me out again.

He didn’t even seem to need to see my face.

Our next stop was a customs official in a glass-fronted booth who didn’t want to see my passport. He didn’t even seem to need to see my face. He just handed me a leaflet explaining the policy from this point on.

The leaflet, printed in five languages, gives simple instructions for waiting for the test results: wash hands, avoid close contact, and so on, but does not mention wearing a mask. It explains what to do in case of a negative result – keep being careful for the first two weeks – and what will happen if the result is positive – a phone call, a blood test and possible quarantine.

We continued to wear our masks the rest of the day, to a supermarket to pick up supplies for dinner and then on to our accommodation, a studio apartment in Reykjavik. We saw no one else in a mask.

Sometime during the night, we each received a text that our tests were negative. Presumably so were the tests of the people sitting near us, since a positive test near to us in the plane could also have sent us to quarantine and/or further testing.

Traveling in Iceland

Note: This article was updated July 28, 2020. Find updated information about travel to Iceland here.

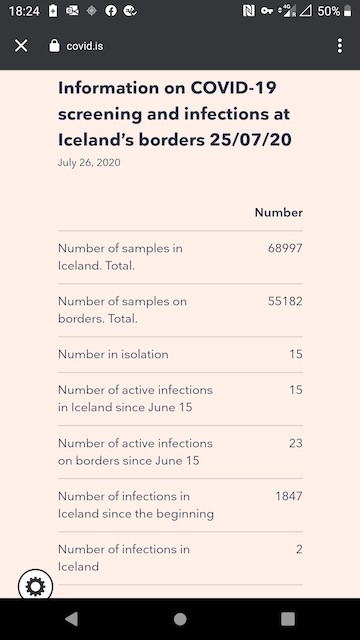

As we travel around Iceland, every day we get a message through the Rakning-19 app telling us the statistics of the day before. As an example, the message we received on July 24 told us that the total number of people tested at Iceland’s borders from June 15 to July 23 was 51,868. Twenty of these were infectious. On July 23, 1843 tests were carried out. Two tested positive for Covid-19. In total, ten people with active infection were in quarantine that day.

- Photo credit: Rachel Heller of Rachel’s Ruminations

People who test positive are then tested for antibodies. If that second test is positive, they are not quarantined, on the assumption that they are no longer contagious. I wonder, though, if this policy is medically sound. Is it sure that people with antibodies can’t still be contagious? And what about the rest of us who tested negative but may still come down with Covid-19 after we arrive?

Meanwhile we continue to sightsee, without wearing masks. We continue to try to keep distance from people, which isn’t hard for the most part. After all, most of the sightseeing here involves things like craters, waterfalls and geysers: things that are outside and take some walking. We travel by rental car, so it’s just the two of us most of the time.

At the same time, every public building we’ve entered in Iceland – restaurants, stores, museums – has signs advocating the two-meter distance, as well as providing disinfectant gel at the door. Yet no one seems to be taking any of it very seriously. Restaurant waiters, for example, aren’t wearing gloves or particularly trying to keep distant. Tables are as close together as always. No one is limiting visitor numbers in shops or museums.

Do they realize, though, that the tests tourists are getting aren’t foolproof?

On an individual basis, we see Icelanders sitting or standing right next to each other and to us in public places: public hot baths, for example, and inside museums. We’ve seen people greet each other with hugs or handshakes. Sometimes the crowds make me so nervous that I feel I have to leave. Yesterday, we visited a turf house, enjoying its warren of small rooms and the displays about traditional Icelandic life. As we entered a long room with old-fashioned beds lining both walls, a group of six or seven people filed in after us, all dressed in traditional Icelandic outfits. They seated themselves on the beds on either side, and more people followed them into the room: tourists from various countries.

An impromptu concert ensued, with a man playing an instrument similar to a sitar, while the women on either side kept themselves busy with knitting and other needlework. Normally I would be thrilled at happening upon this sort of unanticipated local event. This single room, though, of perhaps five meters long by three meters wide, had, I’d guess, about 15 people in it. I held out for two songs with my scarf pulled up over my mouth, then left. I saw no signs that anyone else was concerned.

This isn’t a surprise, really, since Iceland’s numbers are near zero. They’ve never experienced lockdown and had no need to get used to social distancing. Do they realize, though, that the tests tourists are getting aren’t foolproof? Or are they just confident and comfortable with how their government is monitoring the situation?

If you are considering travel to Iceland

Iceland is a place of astonishing landforms, dramatic views, powerful waterfalls and boiling geysers. It draws, in a normal year, two million visitors. We’ve been incredibly fortunate to witness this place with much less crowding. We were able to come here because of a concurrence of fortunate circumstances: Iceland’s sensible testing policy, the fact that we’re both healthy and have no immediate family in a risk group, and that we live in a part of the Netherlands that has had extremely low rates of infection. At the time we left for Iceland, there had been no new cases in our province in more than a month.

Our main fear was that we’d end up on the flight next to someone who tested positive on arrival, which might get us quarantined as well. While in that case we risked losing two weeks of our three-week trip, we decided, after much discussion, that the risk was worth the potential reward.

So these are the things to think about before deciding on a trip to Iceland:

- Do you live in an area with a high infection rate? If so, please don’t travel to Iceland or anywhere else with a low infection rate.

- Do you have vulnerable relatives? If so, perhaps taking the risk of infection on a plane is not wise, unless you can plan a two-week quarantine away from those relatives after you get home.

- Can you take the risk of being quarantined on arrival in Iceland? If your planned trip is only a week or two, you’ll spend the entire time in a hotel room.

- Does your own country impose a quarantine on arrivals? If so, you’ll have to plan that in as well.

- Are you willing to use tracking software? It’s not required, but it’s the right thing to do for your own health and the health of Icelanders. If this presents some sort of moral objection, don’t go to Iceland. The same applies if you are an anti-masker, in which case you might not be allowed on the flight anyway.

Should we have gone?

Should we have gone? As with any travel in a Covid-19 world, this trip has involved some risk, but we’ve been fortunate so far. With the benefit of hindsight, we see that two weeks into the trip we have no symptoms and have heard nothing from the authorities or through the app about infectious contact.

I can’t really be 100% sure until we return home, though, if we have managed the trip without a) getting infected ourselves or b) infecting anyone else. I’m confident, though, that we’ve minimized that risk as much as we can. Whether that makes it a wise choice or not is a judgement call.

- Photo credit: Rachel Heller of Rachel’s Ruminations

Traveling in Iceland in a time of Covid-19, by Rachel Heller of Rachel’s Ruminations. All photo credits by Rachel Heller.

This article was updated July 28, 2020.

For sure. 🙂